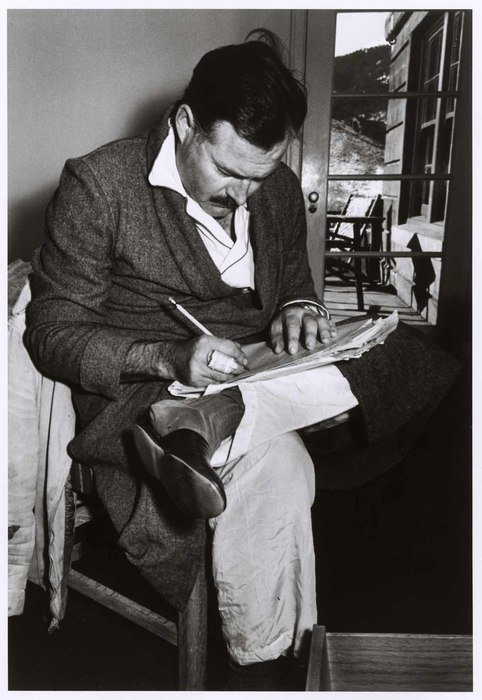

What are you wearing? Sounds like something you’d hear on a cheesy erotic movie, right? Well, when you work from home, as most writers do, you need to think about that.

Are you the sort of writer who likes to get comfortable before you sit down to work? Maybe you don’t even change out of your PJ’s in the morning. Or maybe you change into them before you work in bed. Pajamas are the ultimate in comfort-wear: loose-fitting and soft, just begging you to relax and focus on your manuscript. My PJ’s are an old “Answers.com” t-shirt and a pair of baggy shorts. I usually don’t wear them to write in, though. When I try to write in bed, I get too comfy and end up dozing off…

Or maybe you’re the sort of writer who enjoys dressing up to get to work. Perhaps you need the reminder that this is a job and you should dress the part, as if you’re headed for the office. A no-nonsense business suit will make sure you don’t dilly-dally around and forget the ultimate goal: to finish that novel.

There are even writers who really get into the spirit of things and dress as their characters. I could easily do that. I have a lovely cowboy hat after all, and a period shirt and vest (although I have yet to find a pair of trousers that I really like). Maybe you enjoy a Victorian era ball gown or a morning suit. Or maybe you write science fiction and your outfit is a bit more out of the ordinary…

But you wanted to know what I wear to write. I’m afraid I fall somewhere in the middle. I generally do get out of bed and get dressed, although I don’t dress up. My preferred writing outfit is a comfy t-shirt and a pair of jeans. I usually do put on shoes, too, because I have a bad ankle that needs the support even if I’m just walking to the kitchen for a snack. My t-shirt usually has some sort of logo or sarcastic saying on it, usually fitting my mood for the day.

What about you? What are you wearing?

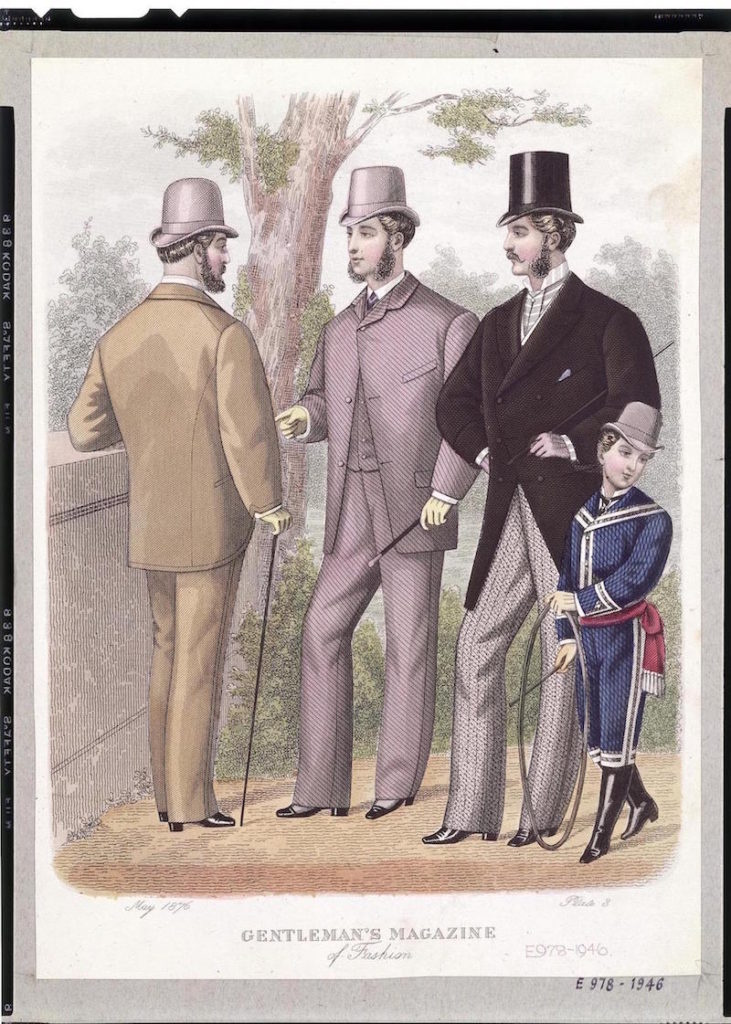

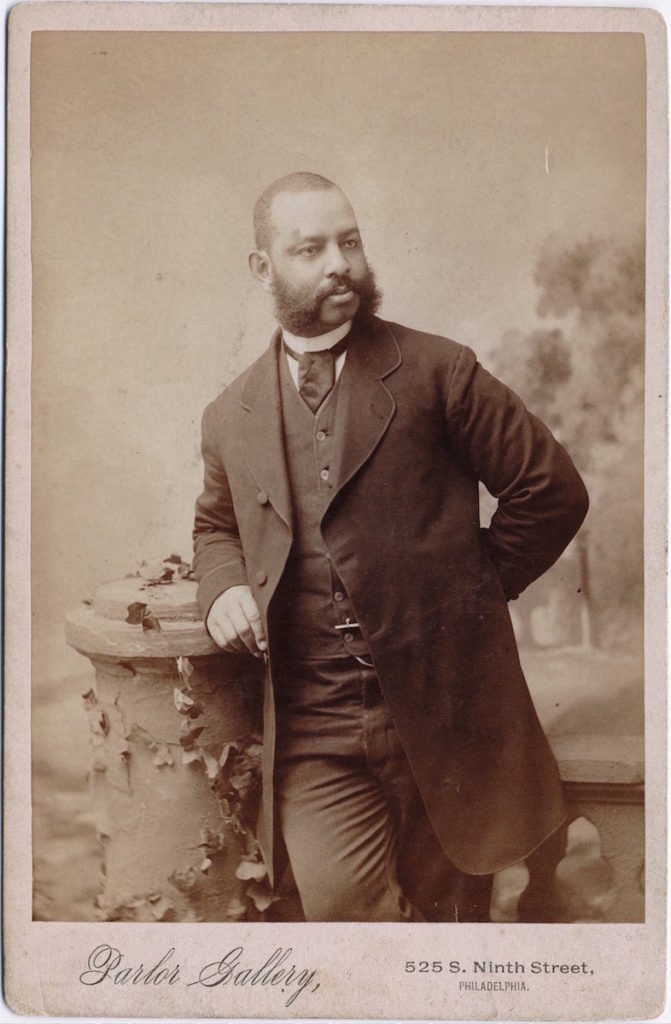

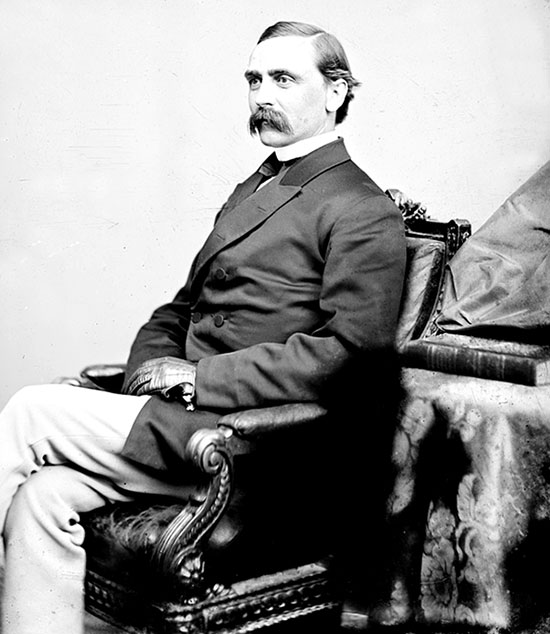

Let’s take a look at men’s fashion during Kye’s and Chance’s era. The 1870s in men’s fashion was marked by “sobriety and understated style.” Nobody was making fashion waves during that time. In 1871, a tailoring journal remarked “Gentlemen dress as quietly as it is possible to do and there are no extremes in dress.” Kye, especially, would have dressed to fit in. Chance would have kept up the latest fashion, but probably in the most expensive fabrics and the most daring styles.

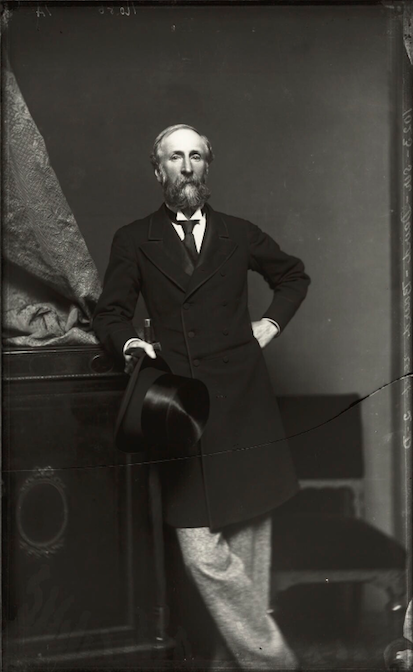

The overall men’s silhouette was slimmed down from the boxy, oversized jackets of the 1860s, with a closer fit and a plain shirt instead of the pleated and heavily starched shirt of the previous decade. This would have made the Wang brothers happy, although it probably meant the laundry bill went down. Formal daywear required a frock coat with a waist seam and a full skirt. In the first half of the decade, the trend was for a shorter frock coat with a hemline well above the knee. Men could also opt for the less stuffy morning coat, a cutaway jacket with a waist seam. This coat, either single- or double-breasted, fastened with three or four buttons and might be bound with silk braid “for an elegant finish.” This was a versatile coat and could appear formal if sewn of dark cloth and paired with gray trousers, or more relaxed if made of tweed. Evening occasions called for a formal black tailcoat (with knee-length tails), a matching double-breasted waistcoat, starched white shirt and bowtie, and black trousers, usually with braid down the outer side seams.

Among the working classes (and probably Kye), the sack coat was becoming more popular. The jacket, with no waist seam, was usually paired with matching waistcoat and trousers and worn with a plain white shirt with a turned down collar and a four-in-hand tie. This was undoubtedly the forerunner of the modern three-piece suit. Chance may have worn a sack coat for lounging around the house. Lapels were either square at the top or cut to form an open “V.” The crease of the turnover was longer than it had been in a while. Sleeves were nearly the same width at elbow and wrist and usually made with cuffs. Trousers were of medium fit and worn more closely fitted to the leg. At the bottom they had a slight gaiter formed by short openings at the bottoms of the side seams. The most popular form of outerwear during the 1870s was the Chesterfield coat, cut knee-length and edged with braid and silk velvet facings. The top frock was an outer garment cut along the same lines as the frock jacket beneath. Inverness and Ulster coats featured capes, sometimes detachable. For sporting events, the double-breasted reefer jacket was becoming popular.

The top hat was the most formal of headgear, worn with frock coats, fancier morning suits, and evening attire. A bowler hat was more often seen with morning and sack suits. Accessories and jewelry were “simple and elegant,” such as a four-in-hand necktie, a silk cravat fastened with a stickpin, and a gold watch chain strung across the waistcoat. Men wore their hair shorter than previously and kept it neatly parted. A clean-shaven face was rare, so Chance would have attracted even more attention than usual. Most men wore full “muttonchop” whiskers or a trim moustache like Kye’s. According to fashion historian Jayne Shrimpton, “the average middle-class businessman carefully avoided exaggerated or effeminate fashions. With a gold watch chain displayed prominently across his waistcoat front, and bushy mutton-chop whiskers or a beard lending an air of authority, the sober-suited Victorian male aimed for a respectable, efficient, industrious image.”

Overall, the look of the 1870s would have suited Chance, being designed to show off a manly figure and display the rich material and elegant accessories that marked the cream of the upper crust. Kye would have been happier in a sack suit, assuming Chance let him out of the house in one. Likely for working on his “filthy contraptions” or blacksmithing. Otherwise, he’d have been bullied into the proper attire for whatever occasion they were attending. What do you think of the 1870s styles? Should they come back into fashion or remain solidly in the past?

I’ve found a great little book for my research: Light and Shadows in New York Life, published in 1872. There’s a chapter that gives some idea of how much a wealthy woman of the time would have spent on her wardrobe. Of course, Miss Emily wouldn’t have been quite as ostentatious, but you can imagine that her gowns would have been pretty close to these prices, due to the quality of the material and the talents of her dress-maker.

Here’s a quote from that chapter – I’ve highlighted what I found most interesting.

Oh, and remember that $1.00 in 1870 would translate out to between $28 and $38 today!

Says a recent writer:

“It is almost impossible to estimate the number of dresses a very fashionable woman will have. Most women in society can afford to dress as it pleases them, since they have unlimited amounts of money at their disposal. Among females dress is the principal part of society. What would Madam Mountain be without her laces and diamonds, or Madam Blanche without her silks and satins? Simply commonplace old women, past their prime, destined to be wall-flowers. A fashionable woman has just as many new dresses as the different times she goes into society. The elite do not wear the same dresses twice. If you can tell us how many receptions she has in a year, how many weddings she attends, how many balls she participates in, how many dinners she gives, how many parties she goes to, how many operas and theatres she patronizes, we can approximate somewhat to the size and cost of her wardrobe. It is not unreasonable to suppose that she has two new dresses of some sort for every day in the year, or 720. Now to purchase all these, to order them made, and to put them on afterward, consumes a vast amount of time. Indeed, the woman of society does little but don and doff dry-goods. For a few brief hours she flutters the latest tint and mode in the glare of the gas-light, and then repeats the same operation the next night.

She must have one or two velvet dresses which cannot cost less than $500 each; she must possess thousands of dollars’ worth of laces, in the shape of flounces, to loop up over the skirts of dresses, as occasion shall require. Walking-dresses cost from $50 to $300; ball-dresses are frequently imported from Paris at a cost of from $500 to a $1000; while wedding-dresses may cost from $1000 to $5000. Nice white Llama jackets can be had for $60; robes princesse, or overskirts of lace, are worth from $60 to $200. Then there are travelling-dresses in black silk, in pongee, velour, in pique, which range in price from $75 to $175. Then there are evening robes in Swiss muslin, robes in linen for the garden and croquet-playing, dresses for horse-races and for yacht-races, robes de nuit and robes de chambre, dresses for breakfast and for dinner, dresses for receptions and for parties, dresses for watering-places, and dresses for all possible occasions. A lady going to the Springs takes from twenty to sixty dresses, and fills an enormous number of Saratoga trunks. They are of every possible fabric–from Hindoo muslin, ‘gaze de soie,’ crape maretz, to the heavy silks of Lyons.

“We know the wife of the editor of one of the great morning newspapers of New York, now travelling in Europe, whose dress-making bill in one year was $10,000! What her dry-goods bill amounted to heaven and her husband only know. She was once stopping at a summer hotel, and such was her anxiety to always appear in a new dress that she would frequently come down to dinner with a dress basted together just strong enough to last while she disposed of a little turtle-soup, a little Charlotte de Russe, and a little ice cream.

“Mrs. Judge —, of New York, is considered one of the ‘queens of fashion.’ She is a goodly-sized lady–not quite so tall as Miss Anna Swan, of Nova Scotia–and she has the happy faculty of piling more dry-goods upon her person than any other lady in the city; and what is more, she keeps on doing it. To give the reader a taste of her quality, it is only necessary to describe a dress she wore at the Dramatic Fund Ball, not many years ago. There was a rich blue satin skirt, en train. Over this there was looped up a magnificent brocade silk, white, with bouquets of flowers woven in all the natural colors. This overskirt was deeply flounced with costly white lace, caught up with bunches of feathers of bright colors. About her shoulders was thrown a fifteen-hundred dollar shawl. She had a head-dress of white ostrich feathers, white lace, gold pendants, and purple velvet. Add to all this a fan, a bouquet of rare flowers, a lace handkerchief, and jewelry almost beyond estimate, and you see Mrs. Judge — as she appears when full blown.

“Mrs. General — is a lady who goes into society a great deal. She has a new dress for every occasion. The following costume appeared at the Charity Ball, which is the great ball of the year in New York. It was imported from Paris for the occasion, and was made of white satin, point lace, and a profusion of flowers. The skirt had heavy flutings of satin around the bottom, and the lace flounces were looped up at the sides with bands of the most beautiful pinks, roses, lilies, forget-me-nots, and other flowers.

“It is nothing uncommon to meet in New York society ladies who have on dry-goods and jewelry to the value of from thirty to fifty thousand dollars. Dress patterns of twilled satin, the ground pale green, pearl, melon color, or white, scattered with sprays of flowers in raised velvet, sell for $300 dollars each; violet poult de soie will sell for $12 dollars a yard; a figured moire will sell for $200 the pattern; a pearl-colored silk, trimmed with point applique lace, sells for $1000; and so we might go on to an almost indefinite length.”

Those who think this an exaggerated picture have only to apply to the proprietor of any first-class city dry-goods store, and he will confirm its truthfulness. These gentlemen will tell you that while their sales of staple goods are heavy, they are proportionately lighter than the sales of articles of pure luxury. At Stewart’s the average sales of silks, laces, velvets, shawls, gloves, furs, and embroideries is about $24,500 per diem. The sales of silks alone average about $15,000 per diem.