In our last post, we introduced a character named Mary Sue. A Mary Sue character is a character, usually female but not always (you can have a Gary Stu or Marty Stu), who is a self-insertion or wish-fulfillment for the author. Mary Sue is perfect: she is stunningly beautiful, amazingly talented, and totally beloved by the original characters in the story. You can already see why people hate her so much, right?

The big question for writers—assuming you want to write rounded, believable characters instead of Mary Sues—is how do you avoid this?

The answer is flaws. Yes, your characters need real, logical flaws to be rounded and not cardboard. I’m not talking about the supposed “flaws” of a Mary Sue, like “her lower lip was too full for true beauty” or “she’s clumsy” (but she’s an amazing warrior with little or no training) or “she’s shy” (but everyone is so drawn to her and wants her advice and wisdom). Those aren’t flaws, they’re red herrings.

Real flaws are character traits that have consequences. If a character really is shy, they will have trouble speaking to other people, especially in large groups. If they’re clumsy, they will not make a good warrior because they won’t be physically coordinated. If they have some sort of trauma in their background, they might suffer from PTSD, which is a debilitating disorder, not a handy “let’s give Mary Sue a flaw” characteristic with a couple of minor problems for her.

Creating realistic, logical, rounded characters is hard work. Some authors just can’t be bothered to do that work, so they come up with Mary Sue instead. However, if you want to be a better, more effective author, you will put in the work and craft the best characters you know how to. And that means researching those flaws to make sure you understand what consequences they will have, then making certain those consequences pop up periodically to trouble your character. This way, not only will your character avoid being a Mary Sue, but they will be even more sympathetic for your readers, who will be biting their nails waiting for those flaws to pop up and ruin things for your character.

What are your favorite character flaws?

If you’re a reader, you’ve probably encountered a Mary Sue (or her male equivalent Gary or Marty Stu). If you’re a writer, the term strikes fear into your heart if you hear one of your characters compared to them. But who, exactly, is this person and why all the hatred?

Let’s see what Wikipedia has to say about her: A Mary Sue is a character archetype in fiction, usually a young woman, who is often portrayed as inexplicably competent across all domains, gifted with unique talents or powers, liked or respected by most other characters, unrealistically free of weaknesses, extremely attractive, innately virtuous, and generally lacking meaningful character flaws. The term was actually coined by Paula Smith in her 1973 parody “A Trekkie’s Tale.” Lieutenant Mary Sue (youngest in the fleet) was the perfect crew member, soon beloved of the whole ship, talented in every area, and doomed to die a heroic death, which was (of course) mourned by everyone.

Mary Sue is usually a self-insertion for the author, who is often an adolescent (or otherwise immature) female. The character:

- Has no real personality because she is “just too good to be true.” Mary Sue has no flaws at all—or she:

- May have an obvious “flaw” like supposed shyness, but in fact everyone is drawn to her.

- Has special powers or talents with little or no training.

- Is loved and admired by everyone, including her enemies.

- Is insanely beautiful, even if she has a “flaw” like “her lower lip was too full for true beauty” or “her neck was too swanlike.” She has a perfect body without working for it and if she does have a scar or other distinguishing mark, it only serves to show her specialness.

- Has the highest IQ possible.

- Gives the best advice possible.

- Is implicitly trusted by everyone, even if she trusts the possible villain (who, of course, turns out to be redeemed in the end).

- Loves everyone—especially all animals—without exception, even if she is “shy.”

- Never makes a mistake. She is always polite, never swears, never loses her temper, etc.

- Is inevitably courageous, never even thinking of her own safety.

- Succeeds at everything she turns her hand to, even if she has never tried it before.

- Is utterly incorruptible.

So why write a Mary Sue if they are so despised? Most Mary Sue creators, as mentioned above, are adolescent or otherwise immature, so they don’t realize they are writing a Mary Sue. Other authors just want to put out a fast book, either quantity before quality or just to see their name on a cover. They’re willing to take a “short cut” in order to get something on a bookstore shelf. Mary Sue is easy to write, as she requires no imagination or real thought. She is a cardboard character cut-out an author can just stick onto the set in place of a more well-rounded character that takes thought and hard work.

Stay tuned for the next post: How NOT to Write a Mary-Sue! Have you ever spotted a wild Mary Sue when you were reading?

In order to read critically, you should know the correct terminology of a work of literature–a novel, memoir, autobiography, history, etc. Here are 9 terms every reader should know before they start reading.

- Title: the title is what the book is called; its name, if you will. A good title should summarize, describe, or entice. It should resonate both with the work inside and with the reader.

- Characters: the characters are the beings in the book, whether they are human, animal, or even inanimate objects. You can learn about these characters through their appearance, their personality, their situation, and the actions they take throughout the story. You can also find out about them by what the author says about them, by what the characters say in dialogue, their movements and actions as they react to their situation. There are four basic types of character in a work: a) Protagonist: this is the “hero” or “sympathetic device to drive a story.” The protagonist is the character most of the situations are happening to. b) Antagonist: this character or force is there to thwart the protagonist’s desires and dreams. They are there to create conflict, without which you have no story at all. c) Confidants: these characters, one of which is the sidekick, are there to support the protagonist’s goal and help them achieve it. d) Love Interest(s): This is the most common type of sub-plot and character. They are the ones who show the protagonist’s vulnerabilities and strengths. This will allow the writer to place stumbling blocks in the protagonist’s way and create even more conflict.

- Setting: the setting is where, when, and in what social context the story takes place. It is often the backdrop but can move to the foreground and become a character in some stories. Setting gives readers a framework for the story so they can identify better with the characters and their world.

- Theme: the theme is the central idea within the story. It generally sends a message, which may show you the beliefs and opinions of the author. Theme is usually revealed through the next term, plot. You can find the theme by asking yourself “What did the protagonist learn?

- Plot: the plot is what happens, a sequence of events that tells the story Most plots occur chronologically, but some have flashbacks to the past and may even jump forward to the future. Here’s how you know you have a plot: An inciting incident taken by the antagonist has negative effects on the protagonist. This action creates a problem that must be solved by the protagonist. This becomes the story goal, the pursuit of which leads to confrontations (conflict) until the protagonist either achieves or fails to achieve the goal. Plots also generally have one or more sub-plots that add texture by showing different perspectives of the main conflict of the story and different aspects of the protagonist’s personality. Sub-plots also test the protagonist’s resolve to achieve their goals.

- Style. this is how the author writes the story. Each writer has their own individual style of writing which can usually be identified by their readers. The author’s word choice, sentence structures, and figurative language choices will describe their style, which will then create the mood, images, and meaning of the story. Style is also guided by the genre the author is working in, the viewpoint they choose for their story, and their intended audience.

- Tone: this is the atmosphere or mood of the story. Tone is “the use of words and writing style to convey an attitude towards a topic. Tone “is expressed through word choice, viewpoint, sentence length, and punctuation.” Tone can be said to be how the author feels.

- Mood: this is how the reader feels. The author uses atmosphere to affect the reader emotionally and psychologically, usually with style and tone. Setting is also often important to the overall atmosphere.

- Intention: One question you want to ask yourself is “Why did the author write this? What was their purpose?” The success of a book is often judged by how well it achieves its purpose, whether that is to entertain or to inform.

Knowing and understanding these terms will help you to read on a deeper level and to question what you’ve read, making it mean more to you.

Let’s revisit a post from several years ago! Once you’ve created your perfect character, you have a new problem on your hands: how to name him or her. This can be a challenge to many writers, especially once you’ve gotten a few hundred characters under your belt in stories or series. How do you come up with fresh names for all of those people?

Here are some tips for you.

For Main Characters:

- Choose an ethnic background – Nowadays, people just name their kids any old name without caring what the name’s history might be, but characters need to have more rationale for their names. If you want a Hispanic character to tote the name Achmed around, you’d better have a good reason for it (and make sure the readers buy into it). Check out this website for some ethnic ideas.

- Choose a name by meaning – don’t just settle for something that sounds good. Pick a name that means something appropriate to the story. In my story “Past Connections,” the two band members have musical nicknames, which took a bit of digging to come up with. It’s worth the time to get just that right name, though. There are plenty of good baby name websites that can help you out; try this website for starters.

- Pick a sound – strong characters need strong sounds, like “K” or “P,” while softer characters need more subdued sounds. Try saying each name out loud to see if it matches your view of the character and their personality.

- Choose a nickname – does your character even have one? It’s best to go ahead and decide, then have certain people use that nickname instead of calling the character by their full name all the time.

- Pick a matching last name – again, mixing ethnicities might be all the rage today, but it might get confusing to the readers, who have been picturing Perdita as an alluring Spanish maiden, to discover that she’s actually a busty redhead from the O’Malley family. Here’s a good site with a variety of surnames to get you started.

- Choose an appropriate name – when writing any sort of historical story, you need to pick names that would have been common for that era. You also need to research the most popular names of each generation. And if your book is set in the current day, for example, you wouldn’t be likely to find a heroine named Hester or Ethel. This is a good website for your search.

- Say the names out loud – sometimes a name that looks great on paper will provoke a laugh when pronounced, for all the wrong reasons. I’m sure you’ve met some real-life people who wished their parents had taken this step before writing their names on that birth certificate.

The Acid Test: once you have a list of possible names, find a friend or relative who has no idea what your characters are like. Ask them to read the names and make some guesses about each character based on those. If their answers are way off base, you may need to rethink the names.

Secondary Characters: if a character is important enough to merit a name, but not important enough to spend a lot of time researching, have a few good name websites bookmarked, and just pop over there to mix and match. Be sure to keep good notes, though – you don’t want a second George Rumpel showing up suddenly in a later novel, after killing him off in your first mystery. I keep a Series Bible for all my stories, with first and last names of any characters who have both.

Here are some more good places I’ve used for name searches over the years:

- Census data for a particular year and region

- Old telephone books, school yearbooks, and any other similar list of names

- Credits on movies and TV shows

- Newspapers and magazines

- Genealogy websites (if they offer free trials)

This website is another good reference to start you on the road to naming your characters. Or, once you have written a few novels, you can do as some other authors do and kill off your fans—have a raffle to see which members of your fan club or mailing list will be murdered in your next story.

What about you? Do you have any great character naming tips to share?

I got this idea from reading the latest issue of Writer’s Digest, so fair warning!

Jane K. Cleland says unreliable narrators have been around since before Arabian Nights was written. The term itself is attributed to Wayne C. Booth, who used it in 1961’s The Rhetoric of Fiction. The unreliable narrator is one who cannot be trusted or believed, whether or not the reader realizes that fact until the end of the story.

There are five basic reasons for unreliability in a narrator:

- The Innocent, Unknowing, or Misunderstood: This category includes children, the developmentally disabled, or anyone who finds themselves in a strange culture. It should be fairly obvious why children, with their skewed views of reality, would make unreliable narrators. Ditto the disabled. They just don’t have the experience or the ability to understand everything that’s happening around them. If you’re raised in another culture, though, the same holds true. You’re missing part of what’s happening because you don’t understand the lingo, the idioms, and the context behind the actions.

- The Guilty: This category not only includes people who actually are guilty, but those who feel guilty, whether or not that feeling is accurate. They are going to try to hide things from the reader, either to cover up a crime or to hide the fact that they’re not living up to their own standards.

- The Emotionally Taxed or Mentally Ill: It’s pretty reasonable that a mentally ill person would make an unreliable narrator, with their off-kilter viewpoint. Someone who is emotionally taxed would, in the same way, view everything through the lens of their emotions.

- The Incapacitated: Drug addicts (no matter what sort of drug they abuse) make unreliable narrators because they share two characteristics: they can’t reliably assess risk and they blame others for their failings. Combine those traits, says Cleland, and you have the perfect unreliable narrator.

- The Paranormal: A supernatural character can appear to be human–or not. They may be a ghost or vampire, or they may be a non-human alien or mythological creature. In any case, they’ll have totally different cultural, emotional, and mental backgrounds than the reader, so they will ultimately be unreliable.

Using these five basic categories, you can come up with scores of situations where your narrator will be an unreliable one. And as Cleland, says, “… these are the deliciously twisty and complex stories readers crave.”

Elizabeth Boyle’s webinar on Secondary Characters was quite informative. Here are some of her points.

First, what do you need secondary characters for?

- Lesson or Role? Your secondary character will be compared to the protagonist by the readers. Will they be a lesson to show the protagonist what not to do – or will they be a role model leading the protagonist the way they should be going?

- Mirror or Foil? Will your secondary character be a mirror-copy of the protagonist, holding up what needs to be seen and learned – or are they going to go against the protagonist and provide contrast? A mirror is a character that shares common attributes and may be part of the protagonist’s ordinary world. They may inspire, or they may be a cautionary tale (see below). A foil is a character that is almost the exact opposite of the protagonist, like Holmes and Watson or Will Turner and Captain Jack Sparrow. They highlight traits by contrast, offer lessons, and force self-examination.

- Help or Hinder? Will the secondary character help or hinder the protagonist? They can do the latter without being an antagonist, you know.

- Inspiration. What about inspiring the protagonist? How will the secondary character cheer the protagonist on and help them reach their goals?

- Cautionary Tale. Or will they show “there but for the grace of God go I”? This sort of secondary character shows the protagonist what they shouldn’t do or be, giving them a glimpse at the way things will be if the protagonist doesn’t change.

- Create Conflict. A good secondary character can create a lot of conflict for the protagonist, often without realizing it.

- Layers. And a secondary character can show different layers in themselves and in the protagonist. Start with the outer layers like clothing and mannerisms and move inward to things like how others perceive them, what is likeable about them, their inner character arc, and major life events or culture.

Of course, your secondary characters don’t have to do just one of the above. They can be multifaceted and perform several roles. You can even use an animal as a secondary character, showing the protagonist’s character by showing how they relate to the animal.

Secondary characters also have great powers of transformation for the protagonist. They can bring internal conflict into play and prod the protagonist to question internal beliefs. This can be done either directly or indirectly, by planting questions, showing evidence, or prodding with speculation.

Here are some archetypes for your secondary characters:

- The sidekick or BFF (Best Friend Forever): this character is a close friend (or family member) who sticks to the protagonist through thick or thin. Think Luke Skywalker and Han Solo or Harry Potter and Ron Weasley.

- The mentor, guardian, or magi: this is usually an older character who guides the protagonist along the way. Think Yoda or Gandalf.

- The love interest: this may or may not be the main romance in the story. A love interest doesn’t even need to be acknowledged by either party, but this character is the one your protagonist is in love with. Will Turner and Elizabeth Swann or Aragorn and Arwen are two good examples of a love interest.

- The skeptic: this character is, as it sounds, one that picks holes in the protagonist’s ideas and plans. “That’ll never work,” or “How can you justify that?”

- The fool: this is an innocent character, not necessarily ignorant, but naïve and usually somewhat bumbling. They show the protagonist the way by stumbling into the wrong answer over and over.

- The tech wizard or specialist: this is a secondary character, like Q in the James Bond stories, who seems to have all the gear the protagonist may need, or some sort of specialized information that may save the day.

- The stranger: this is the character who looks on from the outside of the norm, who can compare the protagonist’s normal life to life in other places.

- The villager: this is the opposite of the stranger, someone from the protagonist’s normal life who can compare life outside with “the way things are supposed to be.”

And as with the above list, your secondary characters can serve several purposes at once. So long as they play off the protagonist in some way, they’ll enhance the story and move things along.

Here are the links to my posts about characters and character-creation:

People ask me where I get my characters. I think they’re either worried that they’ll show up in a book – or maybe hoping for that to occur.

The truth is, I rarely base my characters on real people. Occasionally, I’ll have a contest or oblige a friend and have a “cameo,” but usually, the characters come straight out of my imagination. If you see yourself in any of my characters, that’s great, but it’s not because I know you and decided to toss you in there!

I do use traits from people I know, however. I’ve used a friend’s nervous fidgeting habit, pet phrases, a way of wearing their hair, and other snippets that, divorced from the entire personality, can’t really be traced back to any one person. I don’t like having recognizable people in my stories for several reasons.

First, you’re either going to love it or hate it, and I can’t really predict which most of the time, so why open up that can of worms? Second, this is going to be forever, so whatever I write about you, whether flattering or not, will stick around a lot longer than you want it to. And finally, if I include one real person, everybody’s going to want one – and I just don’t have that many background characters to pass around.

What about you? Where do your characters come from?

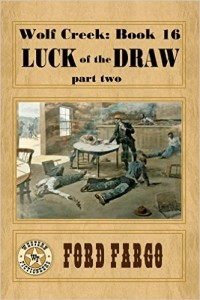

I’ve been invited to create a new character for the Western Fictioneers – something for the shared world of Wolf Creek. This is an 1872 town on the Kansas prairie, with characters created by a variety of authors. We’ve just published Book 16 and my new character will make his appearance in the next anthology.

I thought I’d share a few tips on creating a new character, as I go through the process:

- Start with the basics – first, you need to decide what gender, race and age your character is going to be. This may change later, but start with the basic information in mind so you have that general image.

- Add details – decide how your character looks (at least the bare minimum of hair & eye color, approximate size, and anything unusual) and how they dress. Imagine the outer package for your character.

- Pick a setting – where does your character come from? Where do they live and work? What do they do and how well do they do it? See your character in their natural habitat before you begin your story.

- Fill out a chart (or two) – find one (or more) of those character charts … and you can’t go wrong with mine – just use the drop-down menu above, under Writer’s Toolkit! Fill out the chart(s) to learn about your character’s personality so you’ll know how they will act in your story.

- Christen your child – once you can see the character clearly in your mind, it’s time to pick a name. By this time, you’ll know the sort of name that fits the character best, whether it’s a traditional name to match their ethnicity, a nickname, or something that describes their personality. My character chart also has a few links at the bottom to help you name characters.

And that’s how I came up with my new character, who’s going to be a sort of Junior Chance – young teens, mixed race, very intelligent, and a budding criminal mastermind. He’s going to serve as a connection between the different parts of Wolf Creek, running messages and selling information, performing tasks that may not be quite legal, and generally being a go-between when a citizen doesn’t want to (or can’t afford to) be seen in a certain part of town.

Everyone has a public side that they show to everyone, and a private side that is only shown to their most intimate friends (and sometimes, not even to them!). So what about your characters?

There is a difference between a character trait and a character persona. Your characters, just like real people, will have certain traits that they wish to keep hidden. They have certain facets of their personality that they will strive to disguise. And that can give you a great source of conflict and tension.

Think about people you know: the beefy muscle-man who’s petrified of needles, the soccer mom who runs marathons, and the bespectacled professor-type who’s a secret underwear model. Don’t we all have our hidden sides? Shouldn’t your characters have one as well?

Give your characters some secrets, preferably ones that they either don’t want known, or that aren’t immediately obvious. Perhaps they’re battling their own dislikes when they serve at that soup kitchen line, or perhaps that jock would really rather be reading a good book instead of making that basket.

The fun of a good story is finding characters who seem to leap off the page, and they can’t do that if they’re just cardboard cut-outs.